Beckett

A couple of weeks ago I attended the pseudo-inaugural event of the recently rebranded Scottish Game Developers Association (SGDA) entitled Writing in Video Games. The topic was broader than one might expect, covering writing small indie games - both in terms of story and code - technical writing in the industry and tools that people use, among many other things. One of the speakers, giving a talk on narrative structure in games, was Simon Meek, who won a Scottish BAFTA last year for his game Beckett.

The session was very engaging with a good amount of discussion and sharing happening around the talks, and I got a chance to meet new people and catch up with some I hadn't seen in a while. Some time after the event had ended I found myself waiting on one of the last trains home, tired but happy that I had attended, and full of ideas turning around in my head. I happened across Simon Meek on the platform, who immediately recognised me from the audience and our brief introduction, and we got chatting.

We were headed to the same station, so continued our conversation on the train. It meandered around in the way that a conversation often does with someone you are just getting to know, particularly when it's after midnight, but it was an amicable and interesting chat. We talked about museums, trains, study, Trix the T-Rex, work, video games (of course) and eventually happened upon Simon's work at the V&A. I mentioned that I'd heard about it though Luci Holland, who's show The Console on Scala Radio is the first on national radio to be entirely dedicated to video game music, when she plugged the exhibition during one of her sessions. After probing my interest in video game music a little, Simon reached into his bag and handed me (completely gratis) a vinyl imprint of the soundtrack to Beckett. I was honoured, and very grateful that he didn't ask me if I'd played the game, because I would have had to sheepishly admit that I hadn't!

Today I fixed that.

Beckett is a wonderfully written, intriguing, unnerving interactive story. The titular character is a private investigator, apparently typically landed with missing persons cases. While Beckett's search for a missing boy is the main thread of the plot, the real story goes on within Beckett as he struggles with loss and regret which have all but engulfed his life.

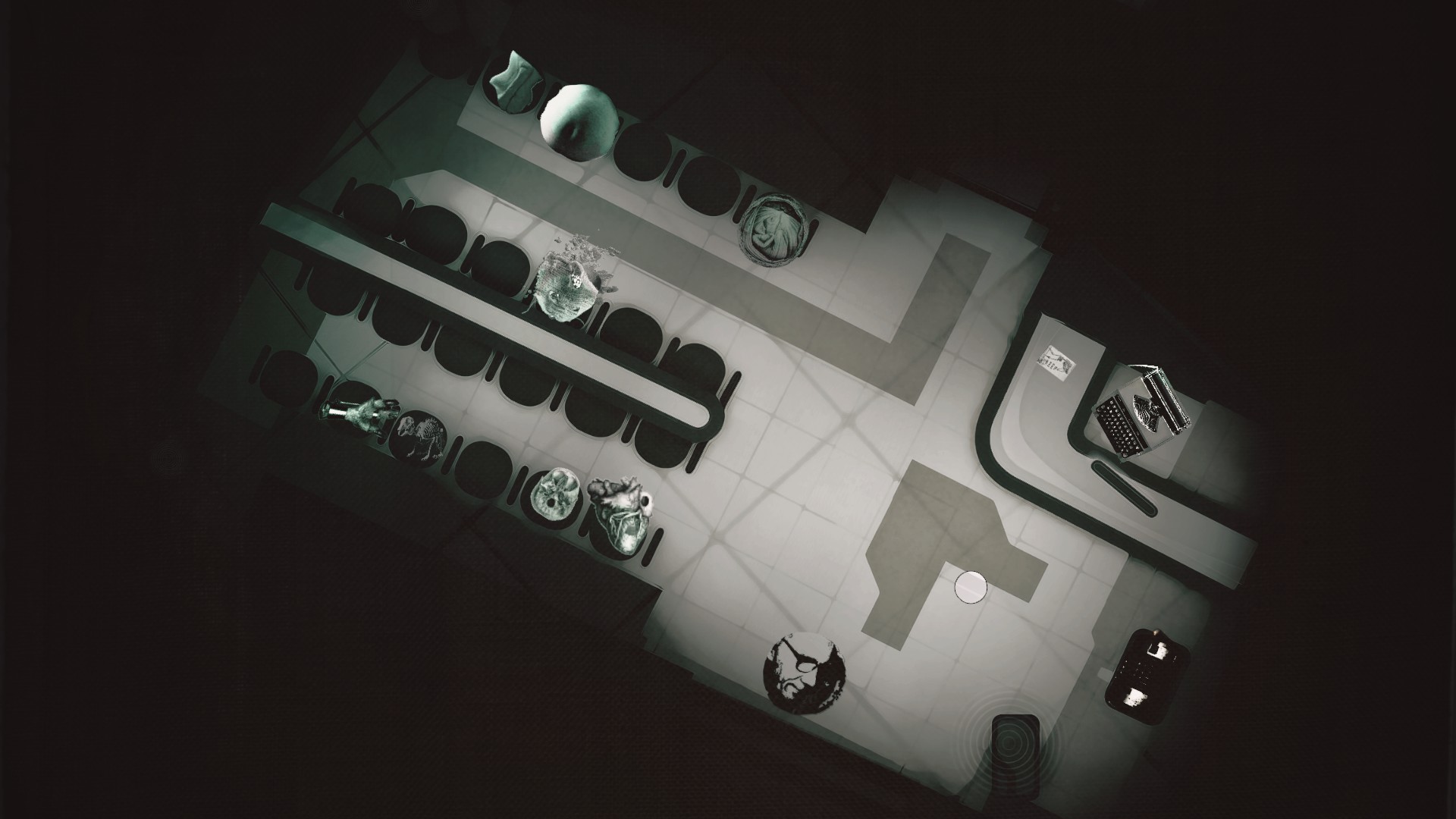

The player tracks through the story with a bird's eye view of the dark, oppressive world represented mostly by crumpled, dirty blueprints stabbed with washes of colour and cut-out images pasted onto the map akin to a scrapbook. The world reveals itself to Beckett as he slowly shuffles through it at the player's instruction, taking us through a bustling marketplace, a decrepit bourgeois house and a musty theatre, just a few of the beautifully realised locations. The game is also beautifully scored and uses audio very creatively, particularly putting spatial sound to good use as cars blare past windows or a hubbub can be heard just off-screen.

The map unfolds, often literally, as Beckett proceeds through it.

Beckett is the only character outside of some of the story panels with a face, and even then it is often angled away, just obscuring enough detail to make him feel truly identifiable. Everyone else is represented by an object and a sequence of "speech" sounds relevant to their character: a gaudy bauble with smacking lips, a dirty glove with snapping garden shears, a theatre mask with chinking coins. This feels to me like it brings out the nature of these characters through Beckett's eyes: fundamentally unknowable and obscured, characterised by whatever stands out to him in the moment.

Other than drive Beckett through what is a primarily linear story, the player has few decisions to make or gameplay actions to perform. He doesn't bend to the player's will: he's his own character, with his own motivations and reasons for his actions. It was refreshing not to be presented with a righteous, saccharine character with their glowing virtue exposed, or a ghostly shell just waiting for me to imprint my own morality on them. These concepts may well have their place in games, but certainly would have been out of place in a story so steeped in history which has led our protagonist to where he is on the day that the player appears.

One might question, then, what the point of the player is at all? We don't direct Beckett's actions, not truly; we don't choose what to say or where to go; we don't act as his conscious or graft ourselves onto his personality. I think that our role is Beckett's curiosity: we decide whether he decides to look at that poster on the wall, to observe the couple in the corner, to stop and take in every monument in the park. As far as I can tell, these actions barely affect what happens, but they tell us who Beckett is. They shape our understanding of Beckett and expose his thoughts and memories, without which the game would simply be a strangely moody story about a PI and a missing young man.

The writing in the game is exceptional, weaving characters and environments with very little to work with.

From the very start of the game it is clear that Beckett is damaged, with a rich, haunting history of which we are initially unaware. He feels like a fully-fledged person whose story we are jumping in on at an almost random point: we don't follow the typical video game tropes of guiding him through his most important moments or witnessing his rise to importance. In fact, it is clear from an early point in the game that the most important moments in Beckett's life are far behind him, and mostly draped with anguish and regret.

The game Beckett is Beckett: slow, meandering, shrouded in darkness and shackled to misery. It hides it's past behind layers of obscurity and reveals them in disjointed segments, much like Beckett pushes them from his mind and hides them away. When Beckett is stressed or panicking, the game thrusts text into your face while colours flash around it and the music and sounds reach fever pitch. When Beckett finds moments of peace, the game quietens and slows. Of course, many games do this, with contextual music and screen effects, but never before have I seen such a strong connection between the behaviour of a game and the feelings of the protagonist. It's very effective.

The characters in the strange world of Beckett are still very familiar as people, dealing with unemployment, bureaucracy, guilt, loss and failing mental health.

Simon's talk shows through strongly in the excellence of Beckett. He implored us - all potential narrative writers - to think about characters and their motivations, not to invalidate their long lives up to the point that the player takes over by having them do whatever the player wants, regardless of the experiences that would have shaped them. He urged us to weave their own lives into the direction of the player, to identify the place where the player belongs: are they to act as the character would act, or as they would act?

In a time where games have a tendency to make inclusions because they're trendy or seem to be expected, broadly regardless of the genre, Beckett was a breath of fresh air. It was succinct and effective, making me feel lots of things about love and loss, and making me think in a more meta sense about narrative and characterisation - just like Simon wanted. I hope we happen to meet again, on a train platform or otherwise, so that we can discuss Beckett in depth. And I hope I've convinced some people reading to give it a try too!